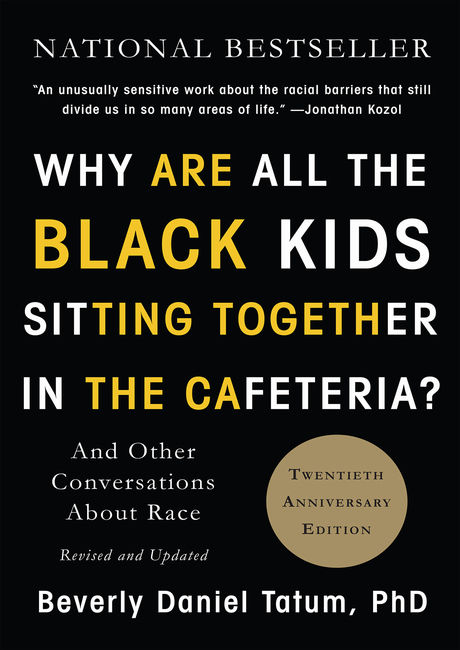

Why Are All The Black Kids Sitting Together in The Cafeteria? (1997, 2017) by Beverly Tatum, PhD

- Adam Nunez

- Dec 3, 2020

- 5 min read

Updated: Dec 7, 2020

Introducing readers to issues of race strategically and thoroughly

Beverly Tatum's book has already received a lot of positive recognition and critical acclaim. It requires little critiquing from me, however, it does deserve more publicity and a place in any conversation about race related issues in the US. The subtitle says a lot: And Other Conversations About Race. In this updated version Dr. Tatum covers a lot of ground with topics such as developing a racial identity through different stages of life, multicultural families (including adoptive families), understanding Whiteness, Color-blindness and other race ideologies, critical issues for other minority groups, and the impact of Trump’s administration on the country. She hardly sacrifices breath for depth, but she does give hundreds of resources if a reader wanted to do more research on a particular topic.

Dr. Tatum was the president of Spelman College in Atlanta,Georgia for many years and taught courses on racial issues, one titled Group Exploration of Racism. In all she has 40 years of experience educating and writing about racial matters. Her personal experiences as an African American woman, mother, and educator shine through this book. She offers a plethora of qualitative studies that are hard to dispute. But if you’re not convinced by the hard data–or where there are no qualitative means to measure racism–then her abundance of personal stories and students’ accounts of racism are even harder to snub. She carries a compassionate and firm tone–like a mother who has no choice but to report unfortunate and sometimes unfathomable news to her children.

She starts by defining racism, giving two common definitions: “a system of advantage based on race” and “privilege plus power” (p. 86). With the latter definition some of her White students have argued that they personally are not prejudiced and they lack power, both of which could be true. She prefers the former since “like other forms of oppression [racism] is not only a personal ideology based on racial prejudice but also a system involving cultural messages and institutional policies and practices as well as the beliefs and actions of individuals” (p. 86). She is keen on discussing all issues from different angles–the personal, political, and cultural.

In the Prologue Dr. Tatum shares the response she often got from people after telling them she was writing an updated version: “Is that still happening?” or “Are things getting better?” (p. 1). She acknowledges that a quick glance at most racially mixed school cafeterias would suggest that yes, things have improved. And twenty years ago it was a lot harder to find a Black or Latina Barbie. And we finally see more minority and LGBTQ groups represented in television and movies.

But she still wonders: “What does ‘better’ look like? That is a more complicated question” (p. 1). One simple fact is that there would be no reason for an updated version if all racial problems were a thing of the past. She highlights a steep increase in hate crimes towards Blacks, minorities, and LGBTQ people soon following President Obama’s 2008 inauguration. She recalls a “postelection Facebook post by a university of Texas student that called for ‘all the hunters to gather up, we have a n––– in the white house.’” With this and other examples, she poses how this “seemed perplexing among a generation of students that voted enthusiastically, two to one, for Barack Obama” (p. 17). Here and throughout the novel with the scalpel of a trained psychologist she digs deep into the psyche behind our human fear of the unknown:

“a shifting paradigm can generate anxiety, even psychological threat, for those who feel the basic assumptions of society changing in ways they can no longer predict...67 percent of Americans expressed pride in the racial progress the election represented, even if they did not vote for Barack Obama. Yet 27 percent of the poll respondents said the results of the election ‘frightened them’” (p. 17).

While we shouldn’t draw too many conclusions from one survey or one presidential election, it’s ludicrous to ignore 358 pages of earnest, clear, and logical reasoning about the negative impact of racism in our country today.

I’d be curious to read a survey about who is purchasing Cafeteria. In the chapter on White identity Dr. Tatum states, “People of color learn early in life that they are seen by others as members of a group. For Whites, thinking of oneself only as an individual is a legacy of White privilege” (p. 196). And later, “As we have seen, many Whites have been encouraged by their culture of silence to disconnect from any racial experience” (p. 338). She also shares how conversations about race are more common for African Americans and other minority families compared with White families, therefore, making discussions about race harder for White people. This unfortunately stifles many conversations about race since White people become easily offended or overly defensive–maybe not lacking empathy since they could very well be good people, but lacking the patience to listen and learn even when they may not always agree.

So, no matter your race, this is a book for everyone. But for some African Americans, Dr. Tatum’s news will be old news. From an NPR program I’m paraphrasing a quote from author James McBride: Nothing is really a problem until White people recognize it as a problem. This makes Cafeteria important for all people to read, but imperative for White people.

At one point Dr. Tatum mentions how educators are more likely than others to recognize racism as a real problem–seeing first hand inequalities in education and witnessing race-related stresses on their students. So, teachers and school administrators read this book. Also, parents of a multiracial families, social workers, counselors, or anyone who cares about the well-being of their fellow human beings would also do good to carefully read it.

Her analysis of Donald Trump’s fear mongering tactics and White supremacist inspiration will make you nauseous. Her recounting of numerous violent police interactions with Black people will leave you feeling appalled and angry. Overall, you won’t walk away from this book feeling the same as before. And you definitely won’t agree with everything. But that’s fine. At least you’re taking a step in the right direction. I have about two dozen tabs and annotations of sad faces, happy faces, stars, exclamation points, or WTF’s on every single page. This brings us back to the opening question: Have things improved from 20 years ago? Considering that my sad faces outnumber my happy ones four to one, the answer is yes, but not much. She does leave us with some hope, however. Her final chapter “Signs of Hope, Sights of Progress” are full of success stories from real people doing real things to make positive changes.

Highest Score - 5 Trophies

Writing: 🏆🏆🏆🏆

Readability: 🏆🏆🏆🏆🏆

Argument: 🏆🏆🏆🏆🏆

Overall: 🏆🏆🏆🏆🏆

December 3, 2020

Comments